To Hell and Back (film)

| To Hell and Back | |

|---|---|

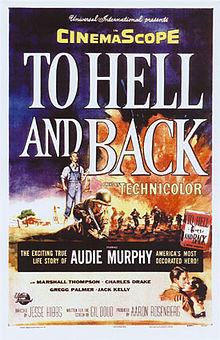

Film poster by Reynold Brown | |

| Directed by | Jesse Hibbs |

| Written by | Gil Doud |

| Based on | To Hell and Back 1949 book by Audie Murphy |

| Produced by | Aaron Rosenberg |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Maury Gertsman |

| Edited by | Edward Curtiss |

| Music by |

|

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 106 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $500,000[2] |

| Box office | $5,799,852 (US and Canada rentals)[3][2] [a] |

To Hell and Back is a Technicolor and CinemaScope war film released in 1955.[4] It was directed by Jesse Hibbs and stars Audie Murphy as himself. It is based on the 1949 autobiography of the same name and is an account of Murphy's World War II experiences as a soldier in the U.S. Army.[5] The book was ghostwritten by his friend, David "Spec" McClure, who served in the U.S. Army's Signal Corps during World War II.[6]

Plot

[edit]Young Audie Murphy grows up in a large, poor sharecropper family in Northeast Texas. His father deserts them around 1939–40, leaving his mother barely able to feed her nine children. As the eldest son, Murphy works from an early age for his neighbor, Mr. Houston, a local farmer, to help support his siblings. Murphy and Mr. Houston are interrupted while working and listen to the radio announcement about the attack on Pearl Harbor. When his mother dies in 1941, Audie becomes head of the family. His brothers and sisters are sent to an elder sister, Corrine. Murphy is then convinced by Mr. Houston to enlist in the military to support himself.

Murphy is rejected by the Marines, the Navy and the Army paratroopers due to his small size and youthful appearance. Finally, the Army accepts him as an ordinary infantryman. After basic training and infantry training, Murphy is shipped to the 3rd Infantry Division in North Africa, as a replacement. Because of his youthful appearance, he endures jokes about "infants" being sent into combat. His squad mates include: Johnson, a man who claims to be a womanizer; Brandon, a man who ran out on his wife and daughter; Kerrigan, a man who jokes at unusual times; Kovak, a Polish immigrant who wants to become an American citizen; Swope (called "Chief" by his squad mates), a Native American who smokes cigars a lot; and Valentino, who has relatives in Naples.

After the 3rd Infantry Division lands in Sicily, Murphy and his men come under attack by a German machine gun position. Murphy and his men assault the position and kill the Germans. After fighting in Sicily, Murphy is then promoted to corporal. After Sicily, Murphy and his squad receive a new platoon leader, Lt. Manning. During a diversionary attack on German forces, Lt. Manning is wounded and Sgt. Klasky, his platoon sergeant, dies. This results in Murphy taking command of the platoon. After proving himself in leading his platoon while fighting in Italy, he is then promoted to sergeant. Murphy and his men are then sent to Naples on R&R.

Murphy and his men later take part in Operation Shingle. After landing on the beach, Murphy and his men fight around an abandoned farmhouse. This battle results in Lt. Manning, Kovak and Johnson being killed. After the Allied breakout of Operation Shingle, Murphy and his men are moved to Southern France, during which Brandon is killed, and he eventually receives a battlefield commission to the rank of second lieutenant.

The action for which Murphy was awarded the Medal of Honor is depicted near the end of the film. In January 1945, near Holtzwihr, France, Murphy's company is forced to retreat in the face of a fierce German attack. However, Murphy remains behind, at the edge of a forest, to direct artillery fire on the advancing enemy infantry and armor. As the Germans close on his position, Murphy jumps onto an abandoned M4 Sherman tank (he actually performed this action atop an M10 tank destroyer) and uses its .50-caliber machine gun to hold the enemy at bay, even though the vehicle is on fire and may explode at any moment. Although wounded and dangerously exposed to enemy fire, Murphy single-handedly turns back the German attack, thereby saving his company. After a period of hospitalization, he is returned to duty. The film concludes with Murphy's Medal of Honor ceremony shortly after the war ends, as Murphy remembers Kovak, Johnson and Brandon, who were killed in action.

Cast

[edit]- Audie Murphy as himself

- Marshall Thompson as Private/Corporal Johnson

- Charles Drake as Private Brandon

- Jack Kelly as Private/Staff Sergeant Kerrigan

- Gregg Palmer as Lieutenant Manning

- Paul Picerni as Private/Corporal Valentino

- David Janssen as Lieutenant Lee

- Richard Castle as Private Kovak

- Bruce Cowling as Captain Marks

- Paul Langton as Colonel Howe

- Art Aragon as Private Sanchez

- Felix Noriego as Private Swope

- Denver Pyle as Private Thompson

- Brett Halsey as Private Saunders

- Susan Kohner as Maria

- Anabel Shaw as Helen

- Mary Field as Mrs. Murphy

- Gordon Gebert as Audie as a boy

- Julian Upton as Corporal Steiner

- Rand Brooks as Lieutenant Harris (uncredited)

- Robert F. Hoy as Private Jennings (uncredited)

- Harold "Tommy" Hart as Staff Sergeant Klasky (uncredited)

- Hugh E. Davis as British Soldier (uncredited)

Production

[edit]When Universal-International picked up the film rights to Audie Murphy's book, he initially declined to play himself, recommending instead Tony Curtis, with whom he had previously worked in three Westerns, Sierra, Kansas Raiders and The Cimarron Kid. However, producer Aaron Rosenberg and director Jesse Hibbs convinced Audie to star in the picture, despite the fact the 30-year-old Murphy would be portraying himself as he was at ages 17–20.[7] At one point during filming, Murphy allegedly alarmed and scared the film crew and his colleagues when he brought loaded firearms on set rather than using the props that were available, largely believed to be due to the Post Traumatic Stress Disorder he suffered following his service in the war itself.

The picture was filmed at Fort Lewis and Yakima Training Center, near Yakima, Washington with actual soldiers.[8] Murphy received 60% of the $25,000 the studio paid for the rights, as well as $100,000 and 10% of the net profits for starring and acting as a technical advisor.[9]

Release

[edit]The film's world premiere was held at the Majestic Theatre in San Antonio, Texas on August 17, 1955. The date of the premiere was also the tenth anniversary of Murphy's army discharge at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio.[10]

Reception

[edit]Reviews from critics were generally positive, with Murphy receiving good notices for his performance. A. H. Weiler of The New York Times wrote that Murphy "lends stature, credibility and dignity to an autobiography that would be routine and hackneyed without him."[11] Variety wrote that the soldiers were "played with a human quality that makes them very real. Fighting or funning, they are believable. The war action shown is packed with thrills and suspense."[12][13] Harrison's Reports was more mixed, writing that "the mere fact that the story is genuine does not lift it to any great heights as a dramatic offering," and calling the film "well directed and acted" but still "no more than a fairly good war picture entertainment-wise."[14] Richard L. Coe of The Washington Post was positive, writing that Murphy "brings an emotional poignancy that stems partly from our knowledge that he did these daring, unbelievable acts of courage and partly from the skill he has achieved as an actor."[15] Edwin Schallert of the Los Angeles Times was also positive, declaring that the film was "to be highly rated for its honesty in the treatment of its subject, and though it is not a picture that is plotted dramatically, it offers a great demonstration of youthful bravery and character that is inherently both dramatic and dynamic."[16] In a dismissive review for The New Yorker, John McCarten wrote of Murphy, "I am told that he is a modest man, and he behaves modestly here. However, the events described in the picture have a factitious air about them. Maybe the spontaneity of actual heroism just can't be duplicated in the movies."[17] The Monthly Film Bulletin agreed, writing that "although the script is based on Murphy's own account, the treatment is regrettably forced and spurious. Commonplace, 'B' picture direction and a reliance on familiar Service types make the lavishly staged battle scenes appear monotonous, confused, and, at the climax—with Murphy wiping out scores of the enemy singlehanded—not a little ridiculous."[18]

The film was a huge commercial success, further advancing Murphy's film career. He had a percentage of the profits and it was estimated the actor earned $1 million from the film.[19] The movie also popularized a term for U.S. Army foot soldiers, "dogface".[20] The film included the 3rd Infantry Division song, "Dogface Soldier", written by Lieutenant Ken Hart and Corporal Bert Gold.[20][21]

Many of the battle scenes were reused in the Universal film The Young Warriors.[citation needed]

Sequel

[edit]Murphy tried to make a sequel called The Way Back dealing with his post-war life but could never get a script that could attract finance.[19]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Please note this figure is rentals accruing to film distributors, not total money earned at the box office.

References

[edit]- ^ "To Hell and Back - Details". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ a b "Pix Pioneering - 56 style". Variety. 16 August 1956. p. 17.

- ^ Cohn, Lawrence (October 15, 1990). "All-Time Film Rental Champs". Variety. p. M176.

- ^ "U.S.S. Forrestal, 1955/09/01". Internet Archive. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ^ Murphy, Audie (1949). To Hell and Back. New York: Henry Holt and Co. OCLC 2037656.

- ^ "Audie Murphy, Great American Hero," Biography, Greystone Communications, Inc. for A&E Television Networks, 1996 (TV documentary).

- ^ Gossett, Sue, The Films and Career of Audie Murphy, Empire Publishing, 1996, pp. 13, 34, 35, 41.

- ^ Archambault, Alan, Fort Lewis, 2002 Arcadia Publishing, p.98.

- ^ Gossett, Sue, The Films and Career of Audie Murphy, Empire Publishing, 1996, p. 69.

- ^ The Handbook of Texas Music, second edition, Retrieved 1 April 2020 ISBN 978-0876112533

- ^ Weiler, A. H. (September 23, 1955). "To Hell and Back". The New York Times. p. 21.

- ^ "To Hell and Back". Variety. July 20, 1955. p. 6.

- ^ Variety Staff (1954). "To Hell and Back". Variety.

- ^ "'To Hell and Back' with Audie Murphy, Marshall Thompson and Charles Drake". Harrison's Reports: 118. July 23, 1955.

- ^ Coe, Richard L. (September 30, 1955). "Audie Scores In Own Story". The Washington Post. p. 44.

- ^ Schallert, Edwin (October 12, 1955). "Story of Audie Glows on Screen". Los Angeles Times. p. A8.

- ^ McCarten, John (October 1, 1955). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. p. 85.

- ^ "To Hell and Back". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 22 (263): 179. December 1955.

- ^ a b Don Graham, No Name on the Bullet: The Biography of Audie Murphy, Penguin, 1989 p 250

- ^ a b "The Dog Face Soldier Song". Archived from the original on 2011-03-11. Retrieved 2011-03-09.

- ^ Dogface Soldier Song (mp3) Archived 2006-07-24 at the Wayback Machine

External links

[edit]- 1955 films

- 1950s war films

- 1950s biographical films

- American war films

- American biographical films

- American World War II films

- World War II films based on actual events

- Italian Campaign of World War II films

- Western Front of World War II films

- Films based on non-fiction books

- Films based on autobiographies

- CinemaScope films

- Audie Murphy

- Universal Pictures films

- Films scored by Irving Gertz

- Films scored by Henry Mancini

- Films scored by William Lava

- Biographical films about military personnel

- Films directed by Jesse Hibbs

- 1950s English-language films

- 1950s American films

- English-language war films

- English-language biographical films